Why Coal-Rock Gas is Becoming the New Global Energy Focus

Notwithstanding the rapid energy transformation, natural gas will continue to be an important constant of the energy system for the medium term. This is because, according to the U. S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and International Energy Agency’s (IEA) models on decarbonization and renewable energy penetration even in aggressive scenarios, the role of natural gas in electricity, industry fuel and system balancing will remain important into 2030s.

Of course, one has to acknowledge that the big force behind expansion of natural gas in the last two decades- shale gas- is going to age. Declining well productivity, increasing drilling costs, more stringent regulations are some of the major concerns resonating amongst the major production areas today. While at the same time there are structural challenges in terms of energy security since shale has high resource concentration. More importantly, the system’s demand for stability, variety and equity necessitates that energy be obtained using something other than traditional or conventional fossil fuels alone in the future.

Coal-rock gas, has been a focus of interest for many energy concerns because of its economic potential.The discourse encourages attention to deep and unexplored sources of gas related to coal, among which, coal-rock gas is one of the most famous subtypes. Given the complexities of searching for and finding new large conventional gas fields, these sources are used and/or tackled without much difficulty, possess a better mechanism to ensure energy security, and provide interim benefits. All these aspects encourage the coalbed methane producing coal-rock gas to place regular energy-related discourse.

Coal-Related Gas Keeps Receiving the Long-Term Strategic Value

The past ten years have been characterized by the shale gas leading the growth of world unconventional gases, but, in case of coal-related gas, it still holds its prominent place on the map in terms of global energy structure, security, and sustainability. On the contrary, due to the combination of several negative factors such as the decline in the production of traditional energy sources, the rising geopolitical energy risks, and the stricter regulations on methane, coal-related gas is being earmarked for reintegration into long-term energy planning, thus being positioned as a major player for the gas supply to be stable.

Coal-Related Gas Has the Supply Power of Stability

The case of the United States shows that coal-related gas is definitely not a short-term or marginal resource. Prior to the shale gas explosion, coalbed methane (CBM) was a remarkably consistent contributor to the U. S. natural gas market and even at its peak, the share of CBM was quite significant. This long-term stable output points out that coal-related gas is more like a “baseload resource” than a high-intensity, short-cycle unconventional gas source. The stability from this situation, in a strategic way, helps to juggle power structures and to decrease supply fluctuations.

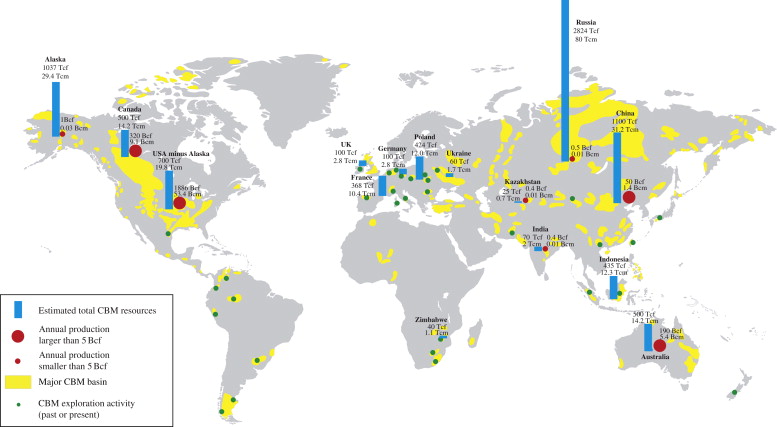

Coal-Related Gas Has a Wide Distribution

Coal-related gas formations are located in many countries around the world ash, Eastern Europe, Australia, and parts of Africa. Coal-related formations are not as concentrated as shale gas which is found only in a few regions. Numerous nations that do not have a large-scale shale gas potential still possess plentiful coal-related geological resources. Thus, coal-related gas becomes a domestic energy source, which leads to a reduction in the dependence on imported natural gas and LNG while also boosting the regional supply’s resilience against market uncertainties.

The Technical Value of Coal-Related Gas is Being Redefined

From an engineering and environmental perspective, it is not only the energy supply that coal-related gas is strategically valuable for but also the controllable methane emissions. Compared to the dispersed leakage from oil and gas fields, methane in coal formations has very specific locations and controllable extraction paths, which provide a practical basis for systematic emission reduction.

In traditional coal mining operations and shallow coalbed methane production, a lot of methane is released frequently as a result of poor pressure control or low efficiency in extraction. By working with the deep coal formations and the characteristics of the gas, the industry is adopting “gas-first, coal-second” or coal-gas co-development methods, where the pre-production extraction effort that leads to significantly reduced uncontrolled emissions is part of the process.

Key Technical Systems for Methane Reduction and Utilization

| Technology | Function | Significance for Coal-Related Gas |

| Directional and Multilateral Drilling | Precisely connect high gas-content coal-rock zones, improving extraction coverage | Boosts gas recovery to make capturing methane a holistic and organized process |

| Multi-Stage Fracturing & Fracture Flow Control | Improve gas flow in low-permeability coal-rock formations | Promotes production from reservoirs with low permeability, thus allowing the extraction to be economically viable |

| Downhole Pressure Management & Real-Time Monitoring | Monitor downhole pressure and gas release | Manages methane emissions, cuts down on unintentional release, and secures operations |

| Surface Gathering & Purification | Collect and purify extracted methane | Allows for the energy supply to be directly integrated with methane, thus making it available for commercial use |

As global methane control regulations become stricter, this engineering strategy—”controlled extraction for emissions reduction”—affords coal-related gas, comprising coal-rock gas, a distinctive technical edge among non-conventional gases, thus facilitating the extensive exploitation of deep coal seams.

Coal-Rock Gas vs. Traditional Coalbed Methane

| Feature | Traditional Coalbed Methane (CBM) | Coal-Rock Gas | Difference & Significance | Technical Development Strategy |

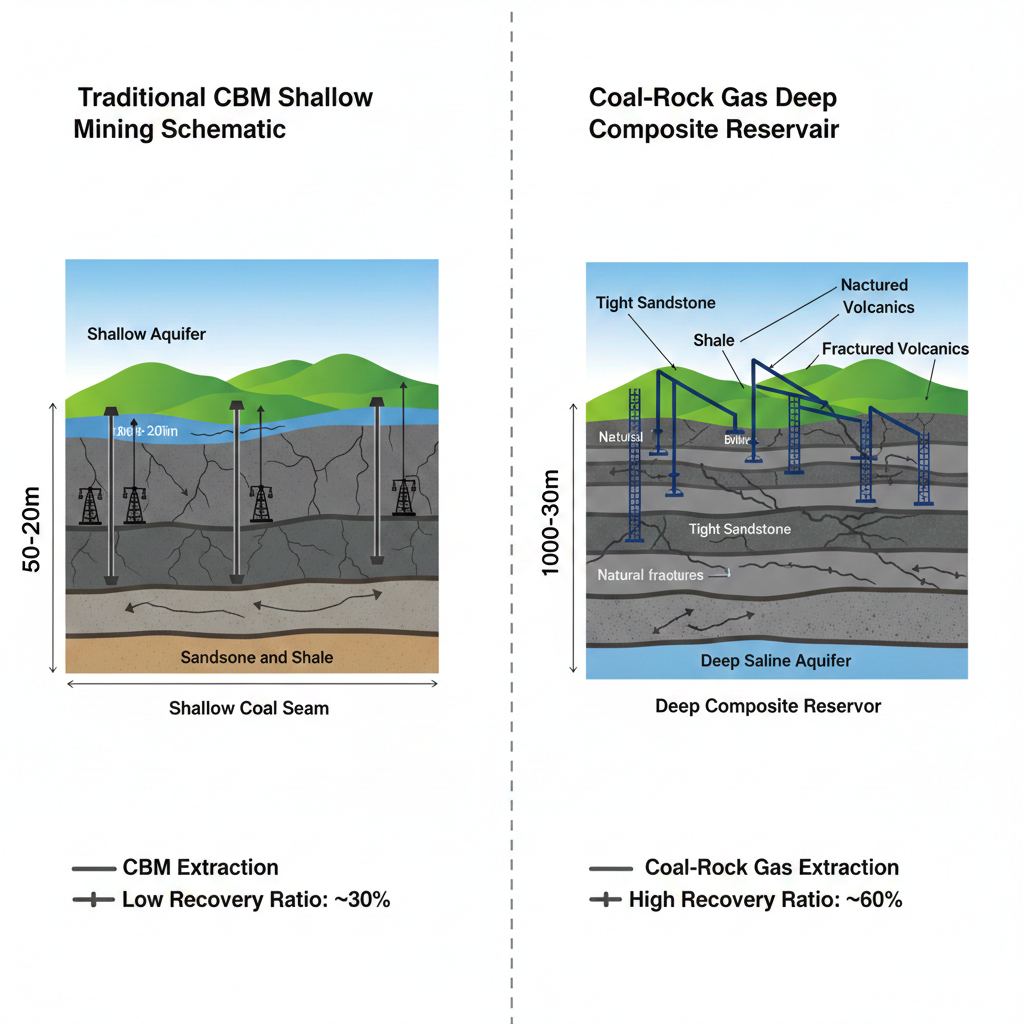

| Depth | Shallow coal seams | Deep coal-rock complexes, usually 1500–2000 m | Greater depth implies higher reserves and long-term production | Deep directional and multilateral wells to cover high gas zones |

| Gas Type | Mainly adsorbed gas | Higher free gas proportion | Higher extraction efficiency, larger initial production | Multi-stage fracturing and fracture flow control for low-permeability coal-rock |

| Reservoir Structure | Single coal seam | Composite reservoirs, including coal, carbonaceous shale, and tight surrounding rocks | More complex pathways for gas flow, larger development space | Detailed reservoir characterization, geological modeling, optimized well layouts |

| Development Mechanism | Pressure drawdown and dewatering | Combines shale gas-style techniques (fracturing, flow control) | Higher operational flexibility, blending coal gas and shale gas advantages | Pressure management and real-time monitoring integrated with modern well operations |

| Development Potential | Limited to shallow seams | Higher potential, unconventional reservoir scale | Complements traditional CBM and shale gas gap | Integrated well network, recovery enhancement, and surface gathering system integration |

Conclusion

Coal-rock gas isn’t a novel idea, but rather a logical step resulting from worldwide energy consumption, advancements in technology, and the changing of climate policies. The U. S. experience has shown that gas associated with coal can indeed be a reliable long-term natural gas supply. coal-rock gas is surfacing as a strategic move towards unconventional gas development due to the decline in shale gas growth and more strict regulations on methane emissions.

In the next couple of years, starting from 2026, coal-rock gas is gradually turning from a “topic of discussion within the industry” to a resource being deployed strategically and integrating in the global energy system.